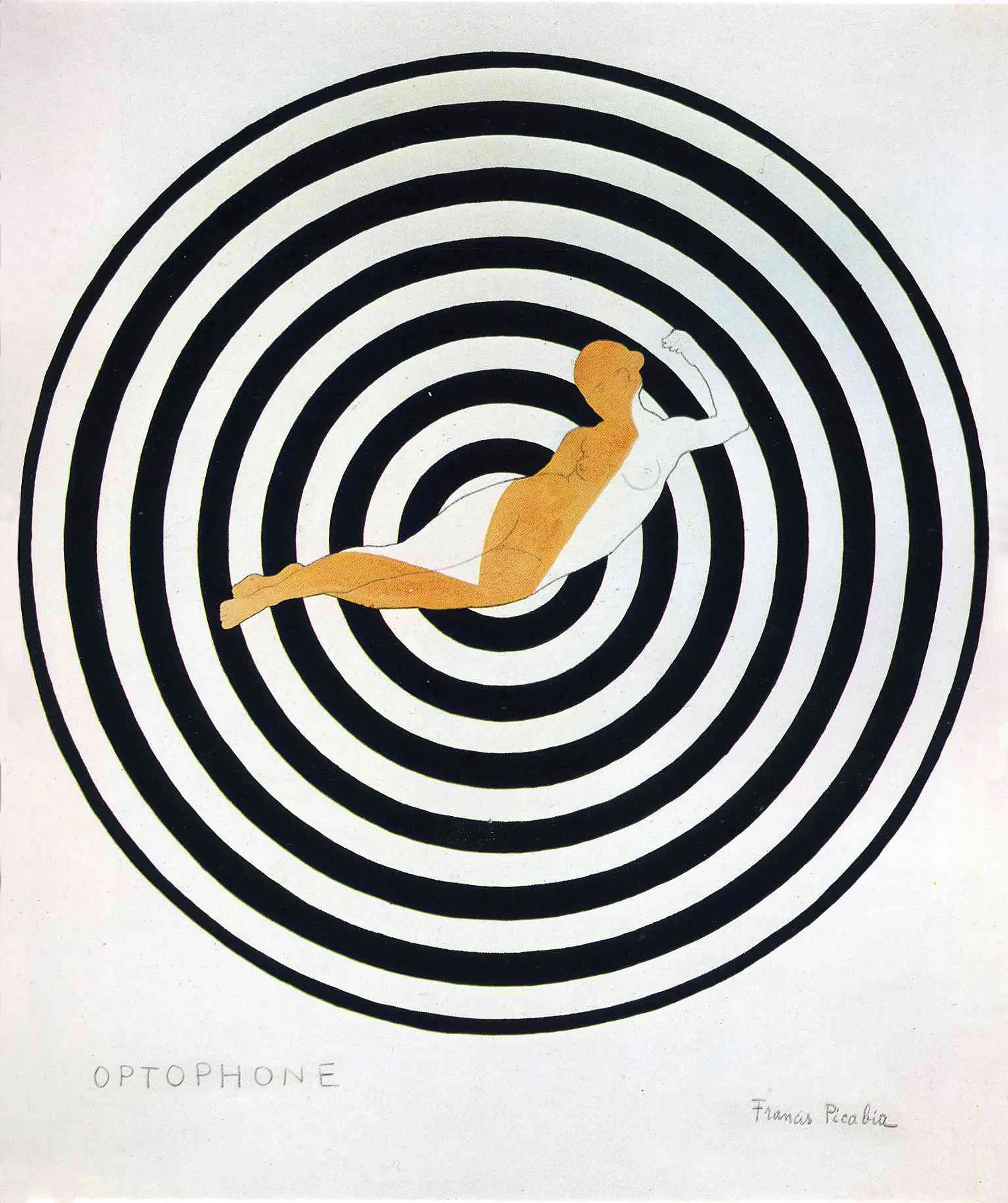

Optophono: Making Music Interactive

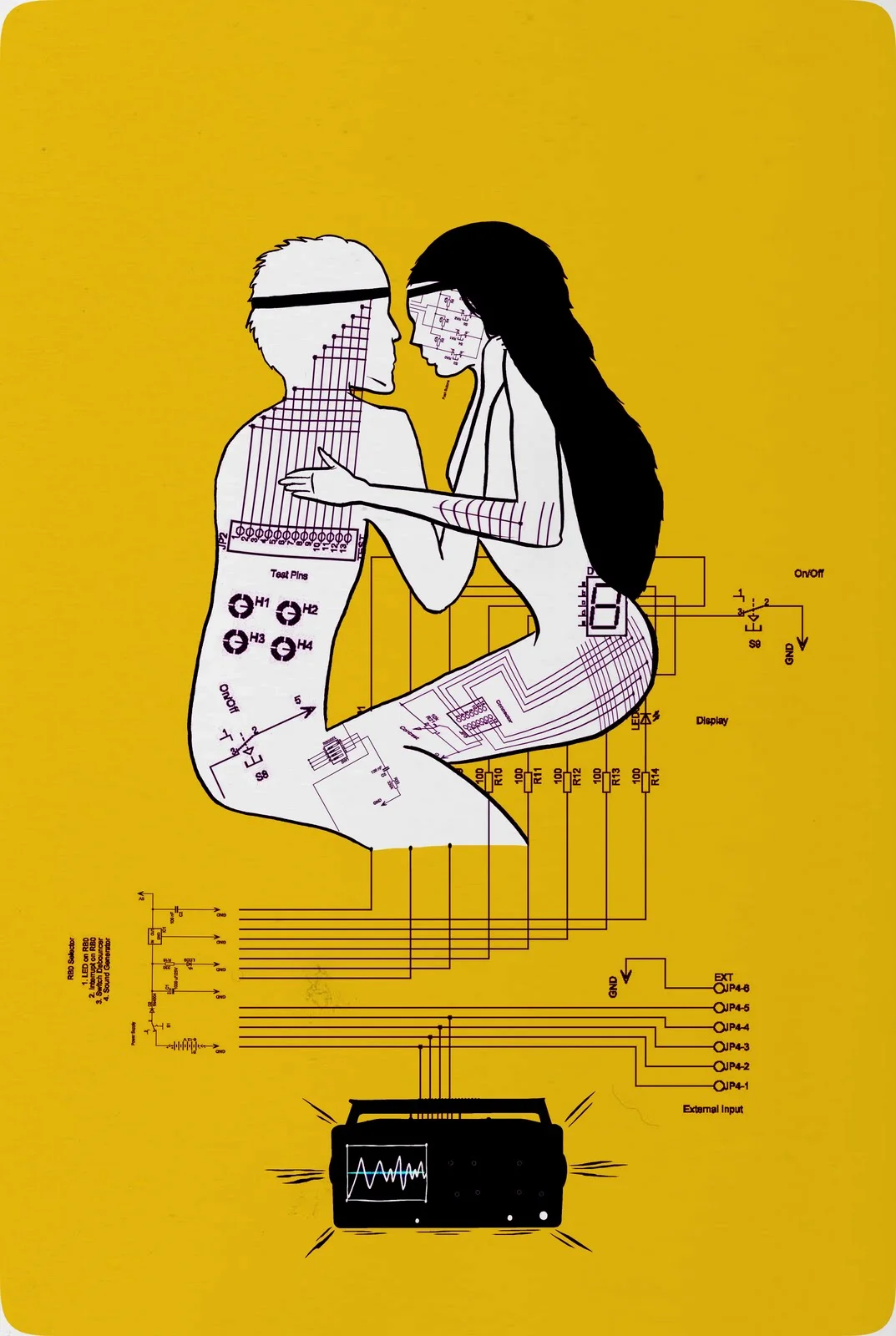

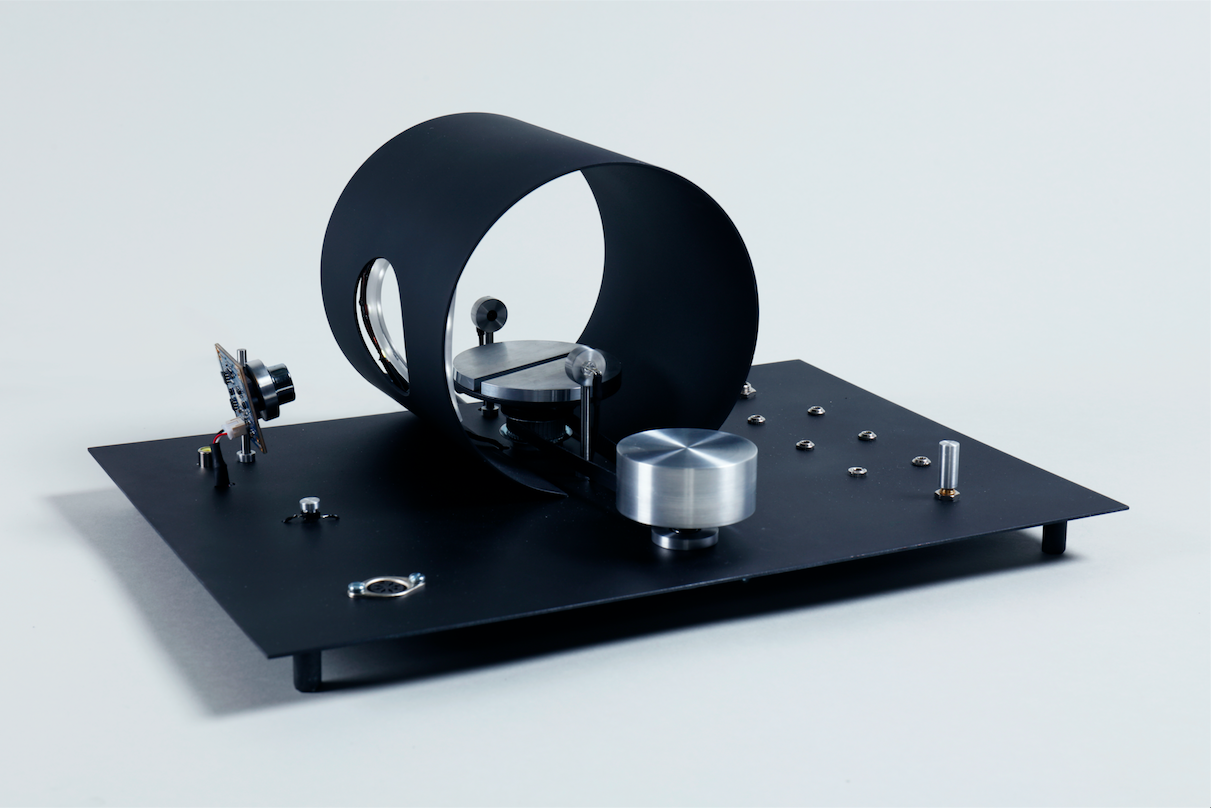

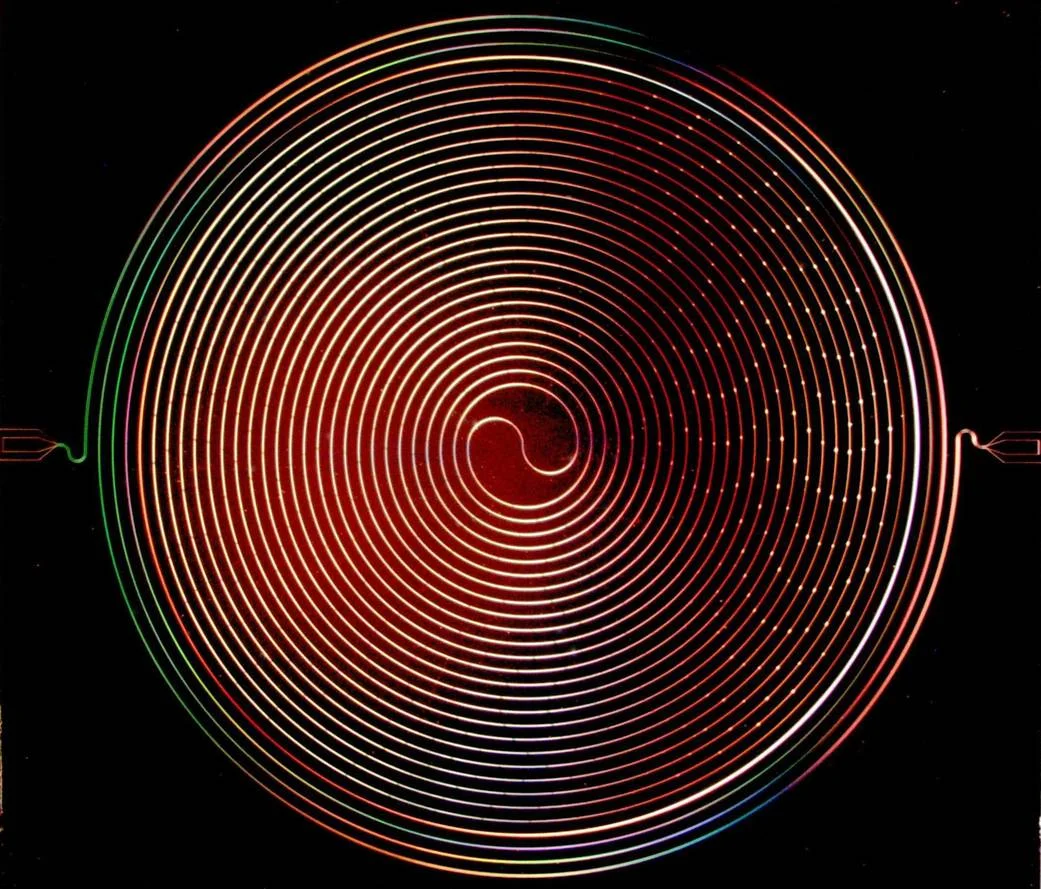

As listeners we have come to think of recordings as something we passively consume. Music is something we press ‘Play’ on—and then do other things while the music ‘happens’. With Optophono we wanted to trouble this dynamic. We wanted to move away from the idea that recordings should be fixed or static objects, and that listeners should have so little creative input into the musical process. Therefore, instead of issuing fixed recordings on CD, tape or vinyl, we created interactive works that we published on hard drives and USBs. These compositions put the listener at the heart of the creative process. Instead of simply pressing ‘Play’ listeners could create their own music using our software and sounds.

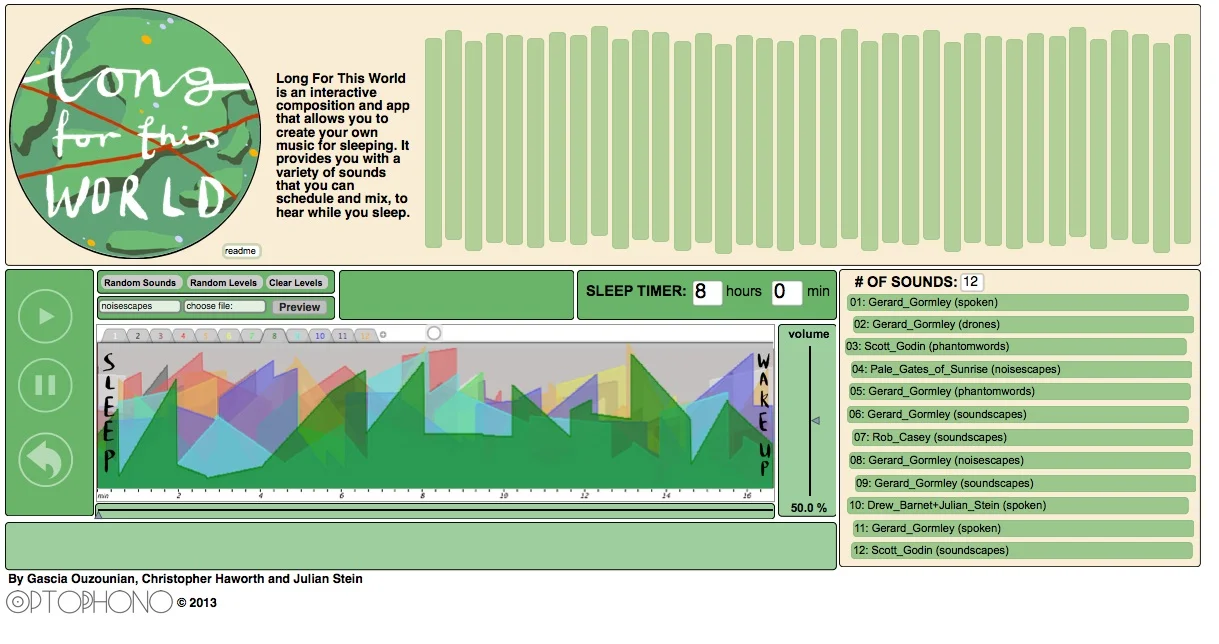

Some Optophono projects have practical applications in addition to being musical compositions. Long for this World, for example, doubles as a sleep app. Using our software, listeners can choose how long they want to sleep for—say, twenty minutes or eight hours—and then create their own music for sleeping. They can do this by mixing dozens of audio tracks contributed by various artists, choosing various randomizing functions, or selecting options from a bank of acoustic effects. The complexity and variety of the music that arises means that not only will every listener have an entirely different experience of the music upon each hearing, but that the listeners themselves will determine, to a large extent, what that music comprises.